Getting down to earth

Some winemakers look to the stars for new ways of ageing their product, as is the case with a Chilean wine, called Meteorito: a Cabernet Sauvignon that was aged in barrel alongside fragments of a 4.5 billion-year-old meteorite. Others, the depths of the ocean. The bottom of the sea is said to act as a time capsule with the ocean maintaining temperature while the currents gently rock the bottles.

South African winemakers are a little more down to earth. There’s been a rise in the use of amphorae for both fermenting and ageing of wines. (Though this is, of course, nothing new – these earthen vessels were used from the get go by ancient Greek and Roman winemakers to ferment and store wine.)

So down to earth, in fact, that Anthony Hamilton Russell looked to his own Hemel-en-Aarde wine estate for amphora material. Back in 2005, Hamilton Russell started experimenting, using a potter to shape the terracotta from his property. “They were too oxidative,” admits Hamilton Russell.

For his next effort, he found stoneware amphorae from Swellendam, which he coated the insides of with a thin wash of the farm’s terracotta—a much more successful and far less porous result. “You get the same level of air exchange as you would in a wine barrel, just not the oak flavour or tannin.”

The resulting wine became a component of several of their Chardonnays. (The Sandstone Ashbourne was almost entirely fermented and aged in the stoneware.)

Winemaker of Grande Provence, Karl Lambour, is a recent initiate to the joys of amphorae. “I think we’ve reached a level in winemaking where we have the confidence to make wine the way they made it 6 000 years ago.”

Over lunch one day with one of his French barrel suppliers he was shown a photo of these “beautiful handmade terracotta pots” made by a family in Florence. Interest piqued, he sourced the pots and started doing his own experiments.

“There’s nothing quite like an amphora for preservation of purity in wine. The terracotta creates an incredibly stable environment and allows you to extract just what you want from the grapes.

“It’s a really nice thing to play with in the cellar. It allows us a degree of creativity that traditional winemaking shies away from. When making wine on a smaller scale, you have the opportunity to experiment and get different textural expressions.”

Lambour was inspired to make a heritage wine. He took Chenin Blanc from a 33-year-old block (90%), along with some hanepoot (10%), destemmed the bunches and placed them all in an amphora for seven months, “letting it do its own thing”. After which, for rounding off purposes, he conditioned it in a “very old” (so that there was no wood influence) 500-litre oak barrel. Ending up with only 600 bottles, he’s thrilled with the result.

"Another Franschhoek winemaker, Clayton Reabow of Môreson has also discovered the joy of working with amphorae and is using both the terracotta jugs as well as the Nomblot eggs.

“I love how wine evolves in amphorae. During fermentation already, the wine progresses and develops secondary characters as opposed to the retention of primary fruit characters offered by stainless steel. Wines fermented and matured in amphorae are very structural as well as textural. It has played a significant role in defining our unwooded Chardonnay by ensuring it remains a unique product year on year.”

Avondale is sticking to their slogan of ‘Soil is Life’ with amphorae made from clay found on the farm. Winemaker Corné Marais says “the combination of oxygen and clay certainly gives the wine a unique character. There’s a definite elegance and earthy minerality.”

Going into the amphorae are some whole bunch Semillon and some Chenin Blanc, as well as some Syrah, Mourvèdre and Grenache.

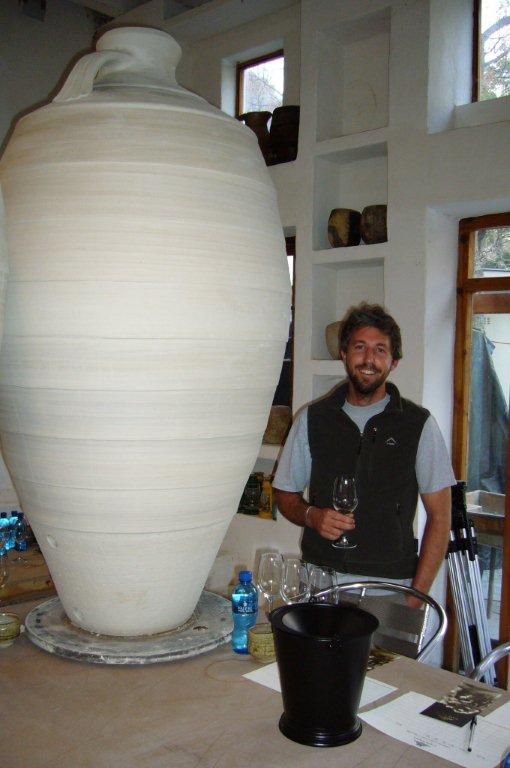

Yogi de Beer, a potter from Hout Bay, is making a name for himself in the wine industry. De Beer, who fired Marais’ amphorae, says he makes them in a few formats. “I use the 600L, which is the biggest,” says Marais.

De Beer turns everything by hand, which takes amazing skill when working with such large objects. After that it gets fired in a kiln.

Another De Beer supporter, winemaker Duncan Savage (Cape Point Vineyards and own-label Savage Wines), kicked off with the Cape Point Vineyards amphora project in 2006. “We wanted to use South African-made pots as opposed to French oak barrels. Yogi guided us to stoneware amphorae and created some of the most beautiful amphorae South Africa has ever seen. The pots are quite oxidative and are fantastic for fermentation with a style less focused on upfront aromatics.”

Savage goes on to say that the pots are also great conductors, which makes managing ferment temperatures et al easy. While over the years Savage has fermented the Cape Point Semillon (and will continue to do so), he’s now added reds to the repertoire. “I’ve started working with Grenache and Cinsaut on the skins in amphorae for up to four months at a time. There is zero working of the reds, we only press them after three to four months and then put them into very old, large format French oak barrels. ”

There are some drawbacks. “The amphorae are extremely oxidative and many batches have found their way to the ‘stook’ tank. And they’re not forklift friendly: a fork through a pot equals disaster.”

Of course, amphorae are being used in the Swartland too. Eben Sadie is using the method for his signature white, the Palladius. He says simply: “It’s about returning the wine back into the earth it came from.”

Just down the road, somewhere between the hay fields, there’s a windswept town called Koringberg. At Wildehurst, winemaker Sheree Nothangel has two amphorae she’s experimenting with too.

These winemakers seem positively jubilant about amphora wines. Corné Marais of Avondale sums it up quite nicely: “There’s a reason why they’ve been using amphorae for thousands of years to make wine.”

– Malu Lambert